Tournament casters are an interesting lot. For most of fishing history, they were among the best known of the American angling fraternity, but in the past thirty years the trend has been to lionize the professional bass fishermen, and to a lesser extent, professional anglers in other fields. It's gotten so bad that even people who profess to have knowledge of our sport are badly ignorant on the notion of tournament casting history and its participants.

That most major tackle makers were tournament casters is not a revelation. Bill Jamison, Fred Arbogast, Al Foss, Hiram Leonard, et al. competed in local, state, and national contests. Men like James Heddon and William Talbot actively supported the sport (Heddon even wrote a monthly column for several years on the subject). But the vast majority of competitors, especially the ones who didn't find success in the tackle field, have been forgotten. I'm going to start profiling a few of these gentlemen.

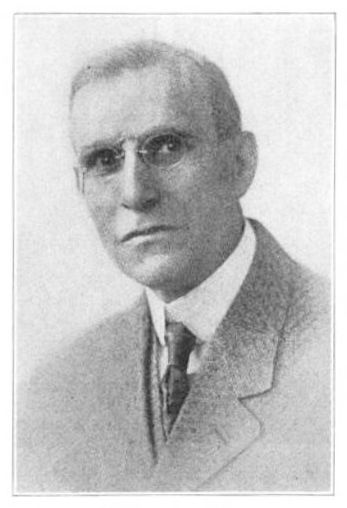

Today's biography is of a long-time Chicago tournament caster by the name of Harry English. English was a member of the Illinois Bait Casting Club, which numbered several dozen members, the most famous of which was William Stanley, a national champion caster and tackle maker of renown. One of their members, H.E. Rice, was the first treasurer of the National Association of Scientific Angling Clubs (NASAC). When the International Fly-Casting Tournament came to Chicago in 1908, English dutifully served on the Entertainment Committee (he was a good tournament caster but not of national reputation). Two years before he had traveled with his friend Charles Antoine, of Von Lengerke & Antoine fame, to Kalamazoo, Michigan to witness the famous casting tournament of 1906.

One of the reasons I like Harry English is that he was not a famous tackle maker. Instead, he was the enormously popular manager of the Reynolds Club at the University of Chicago -- a sort of predecessor to the Student Union idea of the 1930s and beyond. Born on Sep. 7, 1865 in Brooklyn, New York, after numerous odd jobs he gravitated towards club management. According to a 1922 edition of The University of Chicago magazine, on September 29th, 1904, he was appointed manager of the Reynolds Club, about ten months after it was opened. He had previously been in charge of the billiard room (more on that later), and became its first General Manager. English carefully stewarded the Reynolds Club (which required membership) from 300 to over 1,500 members in a short time.

But Harry English was an angler at heart. Even his beloved U of C acknowledged his true passion. "Harry English, of course, possesses a hobby -- fishing. If he could only collect, at one time, all the big ones that 'got away,' the English Fisheries, Incorporated, would be the world's largest firm--maybe. When he retires he expects to do considerable fishing on his Indiana farm."

One of the reasons Harry English is of interest to me is that my job at the University of Minnesota was student manager of the Coffman Memorial Union Recreation Center -- so, like Harry English, I ran the billiards room. One day I will write a book about my experiences there, as I spent an inordinate amount of time shooting pool and meeting interesting people, but one thing I well remember is the general manager of the Rec Center was a grizzled old veteran named Harvey Patzwald. Harvey was in his 70s when I started and a fascinating, if brusque, guy who I got along with splendidly. He reminds me very much of Harry English.

I became a keen student of billiards history as an undergraduate, and read as much about the history of the sport as I could. I learned early on that the famous University of Chicago physicist Albert Michelson -- the first American to win a Nobel Prize in physics in 1907 -- was a dedicated billiards player. As an aside, billiards differs in many ways from pool, as it is played on a larger table that has no pockets with three larger balls. The object is to shoot so that you hit both of the other balls in the same shot, and keep shooting until you miss. It's all about caroms and bank shots and angles. When I ran the Coffman pool room, which in the 1980s had three of the only remaining full-size billiards tables in Minneapolis-St. Paul, the game was popular with Vietnamese gang members who called it Three Ball and wagered huge sums of money on it. I played it often but was never as good at is I would have liked to have been, and not as good at it as I was at nine-ball and eight-ball (which at the time I thought I was better at than I actually was).

Michelson was a brilliant billiards player, just a shade under the quality of the truly great players like Willie Hoppe. He was an intimate friend of Harry English and spent many, many hours shooting billiards in the Reynold's Club pool room. English was, in fact, the confidant of many illustrious figures in University history. The University of Chicago Magazine profile noted, "[University] President Harper…would frequently visit him, and sitting up late at nights in the billiard room, ask all kinds of questions about the Club's affairs and progress."

I don't know if the subject matter of fishing came up, but I do know that Harry English tangentially influenced a very, very important piece of American fly fishing history. In 1928, a young Montana fly fisher came to the University of Chicago as a graduate assistant in English by the name of Norman Maclean. Of course, many decades later Maclean would become famous for his love letter to his Montana youth, A River Runs Through It, but at the time he was a young instructor with lots of time on his hands. He soon made his way to Harry English's Reynolds Club billiards room, which left a lasting impression on him. It is dead certain that he met Harry English (who was famous for greeting the students who frequented his club), and it would have been shocking if there shared love of fly fishing did not come up on a regular basis.

For his part, Maclean would later recount his Reynolds Club billiards days and how he had come to know Dr. Michelson in a wonderful piece written in his inimitable style.

He describes watching the 75 year old Michelson (Harry English would have been 63 when Maclean arrived) shoot billiards, although only "once did he hand me his cue and ask me to shoot, so once must have satisfied him that, although I wasn't good enough to play with him, he could turn to me now and then and lift an eyebrow."

Maclean recalled one time watching Michelson miss a shot, put down his cue, and calculate in his mind the string of successful shots that led up to it until he found where things had started to go wrong. Once he did, Maclean wrote,

He was through for the day. He locked his cue into the rack on the wall, and said, either to me or himself or the wall, “Billiards is a good game.”

He made sure that his tie was in the center of his stiff collar before he added, “But billiards is not as good a game as painting.”

He rolled down his sleeves and put on his coat. Elegant as he was, he was a workman and took off his coat and rolled up his sleeves when he played billiards. As he stood on the first step between the billiard room and the card room, he added, “But painting is not as good a game as music.”

On the next and top step, he concluded, “But then music is not as good a game as physics.”

A beautiful thought, but I'm sure if Harry English had overheard, he would have added, "But then physics is not as good a game as fishing."

The beauty of it is that Norman Maclean lived long enough to realize the wisdom in that final thought. And to that, he owes some small bit of credit to Harry English, the manager of the Reynolds Club and a tournament caster worth remember.

-- Dr. Todd

No comments:

Post a Comment